Turn your fears into a game: Soteria

We are all brave in the context of games – or at least braver than in real life – because we know nothing can really happen to us. (Doris Rusch)

As our experimental platform of choice, we can use games to send players off into alternate universes, make them strike power poses and do epic quests. We can also choose them to address vulnerabilities: Wtf are we doing? Why do we suffer? What’s our problem with being human? Soteria: Dreams as Currency is a point in case.

It uses gameplay to explore the delicate issue of anxiety disorder. As Ana Carmena, an obnoxiously self-loathing steampunk lady, players are first trapped in a hallucinatory nightmare, and learn bit by bit how to cope with Ana’s inner demons.

To learn more about making games about our issues, I talk to Doris Rusch, director of Soteria and founder of the Play4Change Lab at the DePaul University Chicago where she made the game with a team of students.Rusch’s reasons for making a game about anxiety are straight-forward: “I’ve witnessed anxiety close up in my family and know how it can impact people’s lives”. Rusch has been the child of anxious parents, the teacher of anxious students. She has seen anxiety stifle creativity, and sees game design as a possible channel to raise awareness and battle this effect.

Landscapes of anxiety

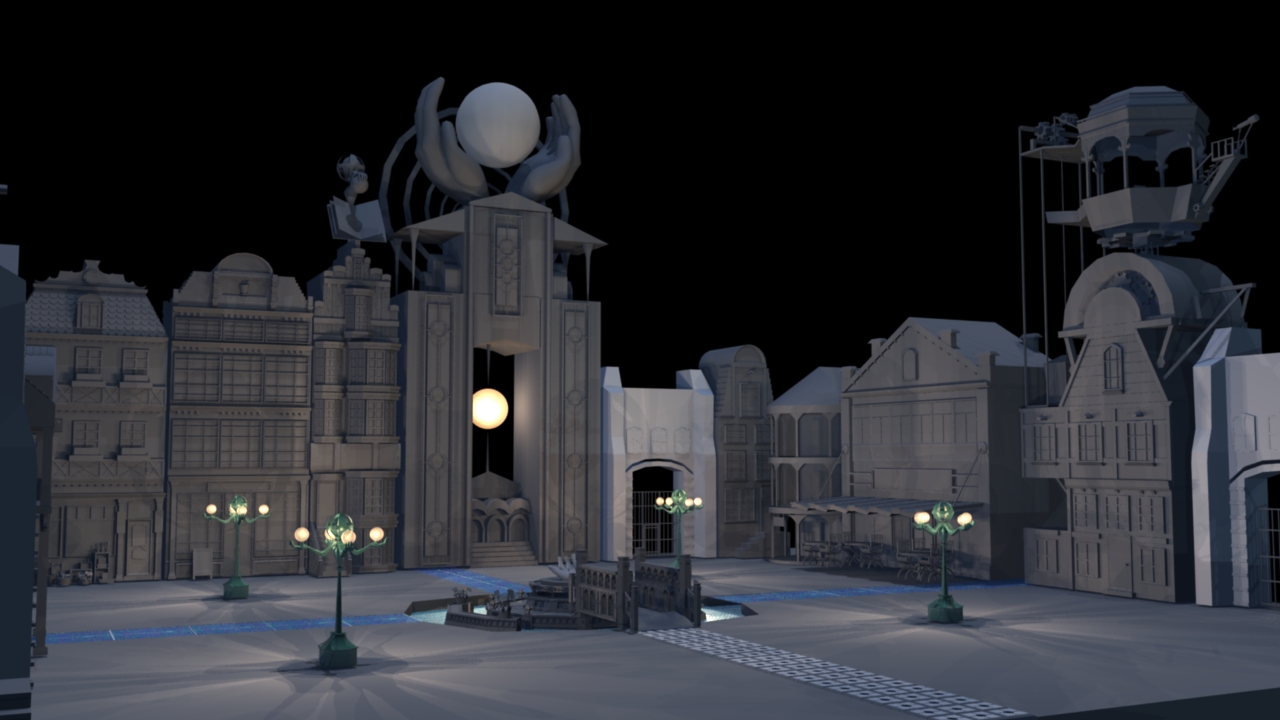

When entering Soteria, the first thing I notice is Ana’s trembling voice. I hear her before I see her. Her sleek polygon body is almost invisible against the dark brown pier whose contours are sharply distinguished from a misty tech-ocean. Ana likes using big words, preferably greek. “Soteria”, the goddess of safety, has called her here. “Oyicis”, the god of fear, has stolen her dreams. I guess what she wants to tell me in half-epic lingo is that she is stuck in a hallucinatory episode and expects me to help.

In the metaphorical landscape of Soteria, we travel through different locations: A disorienting music district infested by disfigured floating ghosts, an eery puppet theatre surveilled by gazing eyeballs, and an observatory room whose navigation chart sends confusing signals. Rusch explains that these locations stand for different aspects of anxiety disorder: The loss of voice and self-expression, the fear of being delivered to the judgment of others, the fear of making wrong decisions. How does Rusch come up with such images? How does she decide on the game mechanics? “It’s not an entirely logical process”, she says. “an image just emerges, usually, and I work with it. I keep digging until something presents itself”.

The lonely harbour is a wondrous blend between spa and steam punk purgatory. When Ana reaches the town square, we hear bland relaxation music while Ana is having conversations on a suspicious bridge-like construction. Ana wants to be safe, but her world is pervaded by a toxic water stream; a blue liquid which Ana constantly has to cross over via numerous bridges. There is a lot of back and forth between observatory, theatre and music district. There is a lot of epic conversation about greek gods we never get to see. And there are enemies; the perennial shadow creatures.

How to get players into anxiety?

We face the first shadow creature as soon as in the start scene, on the pier; a mutilated body slowly floating towards Ana. The game has not taught me to fight such creatures; Ana is weaponless, defenseless. But there is a box suggestively stacked on the side of the dock. When I make Ana approach it, a giant prompt appears [Space to HIDE]. Ana crouches down until the ghost has turned away. I then make Ana sneak away. Sweet escape!

One design challenge was to convey Ana’s anxiety to players in a meaningful way, Rusch says. “We are all brave in the context of games (or at least braver than in real life), because we know nothing can really happen to us”. In the game, fear should be something unsurmountable, something that cannot be overcome. This is why the stealth mechanic is used as the one and only possibility to deal with danger. “The shadow creatures always force Ana to retreat. This conditions players, regardless of their emotional preconditions, to fear the Shadow creatures”, explains Rusch.

Over time, we learn that hiding behind the box is simply what Ana does, what Ana can do, when she encounters enemies. I feel like this is emphasised by the authoritarian, massive “space to [HIDE]” prompt on screen. Just another game instruction we are supposed to follow. Playing “brave” and trying to fight the baddies simply makes no sense. Stealth tactics and sneaking around is how one plays the game.

Asking the mental health expert

To bounce off her ideas of what anxiety feels like, Rusch collaborated with Reid Wilson. Wilson is the founder of the anxiety treatment center in North Carolina. Rusch describes the first draft of Ana’s character as tougher and more cynical. When Rusch and her team ran the dialogue past Wilson, he said: “no, that’s not how someone with anxiety disorder would think, they’d be way more hesitant and reluctant to go towards the fear.” So Rusch rewrote Ana to become more anxious in the beginning.

However, walking the line between Wilson’s expertise and engaging players proved to be tricky. Not every player has the patience to play until the end, and this could be precisely because of Ana’s uncool attitude. She does not only self-loathe, she constantly expresses it in a whiny, trembling voice. We don’t easily allow such lamenting to ourselves and others in real life. We tend to avoid it, eschew it. As Rusch says, “some people who self-identified with anxiety disorder said “yes, that’s what it sounds like in my head, but I wouldn’t want to admit to it. No one wants to be that pathetic.”

From staying safe to lingering through

Ana’s transition from a very anxious creature to a person trying to liberate herself from her fears is a slow process. Having learned that the way of coping with Ana’s fear is by hiding and avoidance, the encounter with an NPC tailor seems promising. By collecting and trading cards with him, he tailors a custom-made Phobos suit for Ana: The ultimate protective garment made from Ana’s fear-avoidance strategies: Eggshells allowing her to tread carefully, a chameleon to blend in perfectly, and a star map to never lose orientation.

Navigating the space in this suit is safe but pointless for Ana. As she desperately calls out, “I also want to live a full life”. This is only possible if Ana decides to take off the suit and tries something she has never done before.

As Ana mentally commits to a “full life”, all boxes are removed, and a new mechanic is introduced: ”lingering through fear” by pressing “Space” repeatedly. The first confrontations are terrifying. As Rusch describes, players have “just been taught what to do, but very few actually do it at this point!” It is new, after all, that we can actually do something to confront Ana’s shadows. “The message that you can’t do anything about the fear has sunk in. Now, adopting the new strategy and fighting the fear means something.” Facing the shadow creatures and interacting with them directly “has become emotionally hard to do”. When players smash the space bar, “it’s an act of change, not just a gameplay convention to fight the bad guys”.

Enjoy the ride!

What can game designers take away from making a game like Soteria? Rusch says that designing Soteria has left her more aware of how to relate to her own fears. “If I feel myself backing away because I get anxious, I wonder: what would Ana do? And how can I provoke the fear now? It helps. I have a huge fear of driving. But I’m driving! I don’t like it. I have to linger through the anxiety. I have to tell myself: you don’t get me to back away! I’m doing this.” In hindsight, “making the game was therapeutic to me. I recommend people to make their own games about their own issues. It probably helps way more than playing finished projects”.

But Rusch is also skeptical of games’ assumed omnipotence. “Let’s just make a game about this problem and it will fix it. Nah, don’t think so”. Game designers deciding to make games about their issues should check their expectations. “Be realistic with what you can accomplish. Enjoy the ride, because making games is awesome.”

So why make games about our issues? If anxiety is here to stay, why not engage it playfully, and invent characters and worlds which help us go through the day? Drive cars, do the dishes, have love affairs? Rusch recommends to “pick a topic that is really meaningful to you”. Because then it’s the making process that becomes therapeutic. If design is the treatment, we might as well add it to the list epic quests.